Sensory Perception and its Objects (प्रत्यक्ष-प्रमाणम्)

Sensory Perception (Samskrit: प्रत्यक्ष-प्रमाणम्) is considered as one of the primary means of valid knowledge. It refers to the direct experience and cognition of objects through the five-senses, which are regarded as the initial and reliable source of knowledge about the external world.[1]

परिचयः॥ Introduction

The word perception originates from the Latin word “perceptio” meaning receiving, collecting, gathering. This term is derived from the verb “percipere” which means “to perceive, to observe, to grasp.”

In Indian Philosophy, Perception is one of the key means of acquiring knowledge, known as Pratyaksha. Pratyaksha refers to direct cognition or knowledge gained through the senses. It is considered as the mode or means to gain knowledge. In the process of perception, there are some technical terms -

- Prama - Valid knowledge or true cognition.

- Pramana - Means or source of knowledge (eg. Perception, Inference).

- Prameya - Object of Knowledge. The thing or fact which is known or to be known.

- Pramata - The person who gains the knowledge. Knower or the Subject.

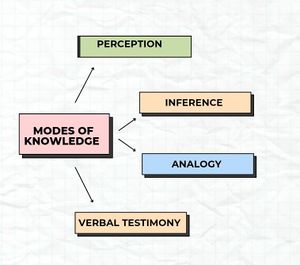

According to Nyayashastra, there are four distinct and independent methods or sources of knowledge, namely, Perception (Pratyaksha), Inference (Anumana), Comparison or Analogy (Upamana) and verbal testimony (Shabda).

- Perception: It means knowledge gained through direct contact of sense organs with objects.

- Inference: In this, knowledge is derived from reasoning or logical deduction based on observation.

- Analogy: When knowledge is gained by comparing something unknown, it is called as Comparison or Analogy. Like saying, a Gavaya is like a cow.

- Verbal Testimony: In this, knowledge obtained through reliable authority or trustworthy verbal statement, especially the scriptures or words of a trustworthy person.

There are certain objects which may be known by any of the four methods, there are other objects which must be known by a particular method and cannot be known by any other. Like, the existence of fire at a distant place may be known from the testimony of a reliable person or it may also be known by inference from the observed smoke as a mark of fire. Or, if we take the trouble to go up to the place from which smoke issues forth, we have a perception of the fire on the spot. Hence, with regard to such objects as the fire, one method of knowledge is as good and valid as any other.

Perception gives us the knowledge of what is directly present to sense and we do not require any inference or testimony for a knowledge of it[1].

किं नाम प्रत्यक्षम् ॥ Definition of Perception

Perception is defined as-

इन्द्रियार्थ-सन्निकर्षजन्यं ज्ञानं प्रत्यक्षम् |[2] Indriyārtha sannikarṣajanyam jñānam pratyakṣam

Meaning: Knowledge arising from the contact of sense organs with objects.

This perception must be immediate, non-verbal, and free from doubt or error to be considered valid.[1]

प्रत्यक्षस्य स्वभावः ॥ Nature of Perception

Nyayashastra emphasizes that perception is:

- Direct and immediate – It does not depend on prior reasoning or inference.

- Based on sense-object contact – Involving the five senses (sight, hearing, smell, taste and touch).

- Cognitive in nature – Leading to awareness or recognition of objects.

There are certain important considerations in favour of the Naiyayika view that perception is the most primary and fundamental of all the sources of knowledge recognised in any system of philosophy. Perception is the ultimate ground of all knowledge. Although perception is not the sole source of knowledge, it serves as the fundamental basis for all other mode of acquiring knowledge. Hence, it is maintained that all alternative means of knowledge depend upon perception and ultimately are grounded in perceptual knowledge. Inference, as a valid source of knowledge, derives its validity from perception. The initial step in the inferential process involves the observation of a mark or middle term (Linga or Hetu), followed by the recognition of its consistent and necessary relation to the major term (Sadhya). Thus, inference is formally defined as that cognition which is necessarily preceded by perceptual awareness (tatpurvaka-jnanam).

Similarly, upamana or comparison serves as a means of knowledge by enabling identification through the perceived similarities between two entities like a known and an unfamiliar object. Through this observed resemblance, the unknown is understood and appropriately named in relation to the known. Also, Shabda or verbal testimony is ultimately dependent upon perception as it begins with the sensory reception of linguistic expression or spoken words, whether heard or seen. The validity of such knowledge depends on the authority of the speaker, who must possess direct or intuitive insight into the subject. Thus, perception stands as the fundamental basis for all forms of knowledge - whether it is inferential, comparative or testimonial. So, it becomes clear that perception underlies all other pramanas, including inference (anumana), comparison (upamana) and verbal testimony (shabda), serving as their ultimate foundation.[1]

यूरोपीय-मतानुसारं प्रत्यक्षम् ॥ The European definition of Perception

In the tradition of European philosophy, particularly among empiricists and certain modern realists, perception is often elevated as the principal and most reliable source of knowledge. According to them, the truth of perception is unquestionable and self-evident as well.

The Naiyayikas, however, do not concede that the validity of perception is inherently self-evident or beyond question. While they acknowledge perception as the ultimate criterion for validating other forms of knowledge, it does not mean that perceptual knowledge is necessarily true or incapable of error. From the standpoint of common-sense to realism, they maintain that, under normal conditions, what is directly perceived is generally not subject to doubt and therefore, does not require additional proof or verification. When however, any doubt arises with regard to the validity of perception, we must need to examine and verify it as much as any other knowledge.[1]

बौद्धमतानुसारं प्रत्यक्षम् ॥ The Buddhist definition of Perception

According to Buddhist epistemology, perception is conceived as the flawless apprehension of a sensory object in complete isolation from conceptual constructs. The Buddhists maintain that the reliability of perception lies in its freedom from conceptual imposition, which is believed to introduce error and subjectivity. By contrast, perceptual knowledge, in its purest form, arises spontaneously through the interaction of the sense faculties with external particulars. This distinction between non-conceptual (nirvikalpaka) and conceptual (savikalpaka) awareness is central to Buddhist epistemology. In this framework, perception functions as a foundational means of valid knowledge because it offers an unmediated encounter with the real.

Buddhists deny the perceptual character of the so-called perception of individual objects like tree, table, etc. In the act of perception, we do not first experience the tree or the table, instead, we perceive a specific quality - such as shape or colour, which is then cognitively combined with prior impressions and related ideas to form the complex awareness of a recognizable object. The Buddhist definition of perception has been criticised and rejected by the Naiyayikas.[2]

जैनमतानुसारं प्रत्यक्षम् ॥ The Jaina definition of Perception

Jain epistemology recognizes Pratyaksha (Perception) as a form of knowledge that is direct and immediate. It is classified into two categories:-

- Mukhya Pratyaksha (Primary Perception) - This is direct knowledge that is entirely independent on the senses and the mind. It originates direct from the self. So, it is free from dependence.

- Samvyavaharika Pratyaksha (Practical or Empirical Perception) – This type of perception is conditioned by the mind and the senses. Though it involves the mind and the senses, it still provides direct awareness of objects.[1]

प्रभाकरमतानुसारं प्रत्यक्षम् ॥ The Prabhakara definition of Perception

According to the Prabhakara school of philosophy, perception is not limited to sense experience only, it is the immediate, intuitive cognition of reality. This includes the simultaneous awareness of the object, the subject and the act of knowing itself without the intervention of inference or representation[1].

अद्वैतवेदान्तमतानुसारं प्रत्यक्षम् ॥ The Advaita Vedanta definition of Perception

In Advaita Vedanta, perception is recognized as a valid means of knowledge (Pramana) and its unique cause (Karana) is the functioning of the sense organs. These organs give rise to a mental modification, which brings about perceptual awareness, this awareness is seen as immediate consciousness (Chaitanya). The role of sense organs lies in producing the mental modification (Antahkarana vrtti) that reveals this immediate knowledge. The antahkarana or mind goes out through the sense organ which is in contact with a present perceptible object and become so modified as to assume the form of the object itself. So, perception is the immediate knowledge in which the mental modification is non-different (abhinna) from the object and it is lit up by the Self’s light. In Advaita Vedanta, the order of the process is, the mind goes through the sense and reaches the object, and there becomes literally changed into the form of the object.[1]

नैयायिकमते प्रत्यक्षम् ॥ The Nyaya definition of Perception

The old school of Nyaya defines perception as knowledge that arises from the contact between sense organs and its corresponding object (indriyārthasannikarṣaḥ). This suggests that perception is fundamentally rooted in the activation of the senses through external contact, indicating that such knowledge depends on sensory stimulation. This definition of perception follows from the etymological meaning of the word pratyaksha or perception.

Modern philosophers do not accept the traditional explanation of perception based entirely on sense-object contact. Gangesha, regarded as the founder of the modern Nyaya, raises several objection to the older definition of perception. He first argues that the definition is too general, since it also applies to inference and memory, where the mind functions as an internal sense in relation to that particular known object. Secondly, the definition is also too much narrow or restricted as it fails to explain the divine omniscience. God’s knowledge is direct and non-sensory awareness of all truth and reality, cannot be explained through the requirement of sense-object contact. If perception necessarily involves the senses, then divine cognition would not qualify as perception at all.

Modern Naiyayikas redefine perception as immediate knowledge. The defining feature of all perception is its immediacy, which is consistently present across different sensory experiences. Another definition of perception, given by the modern Naiyayikas is that it is knowledge which is not brought about by the instrumentality of any antecedent knowledge. This definition applies to all cases of perception, human or divine. At the same time, this definition excludes other forms of knowledge, such as inference, analogy and verbal testimony. Also, memory is dependent on prior direct experience (purvanubhava) for its origin. Perception, on the other hand, does not depend on past experiences in the same way, but that doesn’t mean past experience do not affect how we perceive.

Among the two accounts of perception presented, the modern Nyaya’s perspective is more acceptable and seems easy to agree with. Hence, the modern Nyaya hits upon a truth when it defines perception as immediate knowledge, although it recognises the fact that perception is generally conditioned by sense-object contact.[1]