Rasayana Shastra (रसायनशास्त्रम्)

| This article needs editing.

Add and improvise the content from reliable sources. |

Rasayana Shastra (Samskrit: रसायनशास्त्रम्) referred to the subject of Chemistry based on the chemical activities involved in biological and inorganic processes. It was also called Rasatantra, Rasa Kriya or Rasa Vidya roughly translating to 'Science of Liquids'. "Rasa" in ayurvedic terminology refers to mercury and Rasashastra exclusively deals with the treatment using mercury and its compounds. It is well known that science and technology in ancient and medieval India covered all the major branches of human knowledge and activities, including mathematics, astronomy, physics, chemistry, medical science and surgery etc.

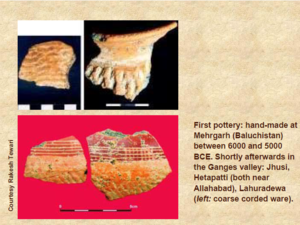

Chemistry is the study of elements present in the universe which involves the nature of the elements, their occurrence, their physical and chemical properties, their compounds, reactivity, uses and applications. Ancient samskrit literary works supported by the archaeological excavations all over the nation have proved the development of this science as early as the vedic period. The earliest evidence of chemical knowledge possessed by the ancient Indians in the prehistoric age has been brought to light by the findings of archaeological excavations in Baluchistan, Sindh and Punjab. The ruins of the Indus Valley Civilization that have been unearthed at in these areas furnish much information about the chemical knowledge acquired by the Indus Valley people, particularly with reference to the practical arts like pottery, brick-making, and extraction and working of metals.[1]

The findings testify to the facts that the people in the remote ages were acquainted with the art of making painted potteries as well as with the preparation and working of metallic copper. Prafulla Chandra Ray was a renowned researcher of chemistry, who set up several chemical industries in Bengal and is regarded as the "Father of Indian Chemistry" in modern times.

One must bear in mind that it is not just India, but several cultures, including non-western cultures around the world that have made several interesting innovations in the fields of chemistry and other subjects. However the present matter pertains to progress of Bharat in several areas of shastras and hence the attention is to bring such lesser known events to readers' knowledge.

Introduction

Chemistry in ancient India, had its origin revealed through the great works of our ancient seers can be attributed to three major areas[1]

- intellectual speculation about the nature and composition of matter (Alchemy)

- development of practical arts to meet the demand for the necessities of life (Dyes, Fermentation)

- self preservation and welfare measures of the society (Ayurvedic preparation)

Ancient India's contribution to science and technology include principles of chemistry which did not remain abstract but found expression in practical activities like fermentation processes, distillation of perfumes, aromatic liquids, manufacturing of dyes and pigments and extraction of sugar, extraction of oil from oilseeds, and metallurgy which has remained an activity central to all civilizations from the earliest ages. Archaeologists' findings of the Indus valley civilization showed a well developed urban system with public baths, streets, granaries, temples, houses with baked bricks, mass production of pottery and even a script of their own which depicted the story of early chemistry.[2]

In pottery making chemical processes were carried out in which materials were mixed, fired and moulded to achieve their objective. In the Rajasthan desert many pottery pieces of different shapes, sizes and colours were found. At Mohenjo-Daro it was found that for the construction of a well, gypsum cement had been used which contained clay, lime, sand and traces of Calcium Carbonate (CaCO3) and was light grey in colour. Burnt bricks were manufactured on a large scale for making houses drains, boundary walls, public bath etc. Many useful products invented were plasters, hair washes, medicinal preparations etc. which had a number of minerals in them and were used by Indus Valley people.

Copper utensils, iron, seals, gold and silver ornaments, and terracotta discs and painted grey ware pottery have all been found in thirty five archaeological sites in North India. Scientific dating of these artifacts corresponds to the non-aryan invasion model of Indian antiquity.[2]

Thus the major chemical products that developed gradually over various eras can be summarized as glass, bricks and pottery, paper, soap, ink, dyeing, cosmetics and perfumes, alcoholic beverages, food processing, pharmaceuticals, mining techniques and alloy preparations, gun powder and saltpetre, and oilseeds. The practical chemists—potters, brewers, dyers, metalsmiths, glassmakers and the like—contributed a great deal to the growth of technology and in no small measure to the economic welfare of the ancient communities. They were noted for their craftsmanship and experimental skills involving many a chemical transformation both qualitative and quantitative, even though they did not appear to have formulated any theoretical knowledge of the chemical transformations.[3]

Alchemical Ideas in the Vedas

Rigveda mentions the Asvini devatas, the divine physicians, who when invoked gave sight to the blind and made the lame walk, restoring people to good health. The Vedas mention many plants, herbs, minerals and metals as the sources of healing powers, used for treating ailments though their potencies are not described. A Rigveda sukta (1.162) gives an account of the bronze cauldron. Gold was used for ornaments like anklets, rings, etc. Mention of metal vessels, tools and armour, seals made mainly of copper, bronze, affords evidence of the knowledge of metal working.[1] According to Rigveda, tanning of leather and dyeing of cotton was practiced during this period. References are found in the Rigveda about the preparation of tanning of leather and hides for use as slings, bead strings, reins and whips.[1]

There are ample references of a number of fermented drinks. Soma, the rasa (juice) is a fermented juice from the stems of soma plant regarded as the Amrita, is said to heal all ailments and bestow immortality. Among fermented liquors, there is a mention of madhu, a drink supplied at feasts, and sura, another drink probably a kind of beer brewed from barley grain. Curds or fermented milk constituted an important item of diet. Clothes were mainly made of wool and the garments were often dyed red, purple and brown; people demonstrated their acquaintance with the art of dyeing with natural vegetable coloring material.[1]

Yajurveda clearly mentions six metals[1] - Ayas (gold), Hiranya (silver), Loha (copper), Shyama (iron), Sisa (lead), Trapu (tin). Atharvaveda names Harita (yellow) as gold, Rajata (white) as silver and Lohita (red) as copper.

Plants and herbs were worshipped for their healing powers. The Atharvaveda mentions the suktas for the cure of diseases and possession by demons of disease are known as "bhaishajyani,' while those which have for their object the securing of long life and health are known as "ayushyani," a term which later on gave place to rasayana, the Sanskrit equivalent of alchemy.[4] While the term itself does not mean chemistry, a study of history of chemistry through the Vedic, Darshana, Tantric and Ayurvedic textual studies reveals the relationship of alchemy and modern day chemistry to the understanding of Rasayana shastra as variously described in ancient texts. Alchemy in India was variously called Rasashastra, Rasavidya; the word rasa has many meanings, such as essence, taste, sap, juice or semen, but in this context refers to mercury, seen as one of the most important elements.

Origin and Properties of Matter

Chemistry dealt primarily with the composition and changes of matter and the underlying principles were deduced in a systematic and logical way purely based on thoughts with little or no experimental proofs. Yet many such theories, the products of intellectual perfection and sublime intuition, stand in good comparison with some of the most recent and advanced scientific ideas of the present time. Chemistry involves the study of fundamental properties of matter and atoms, and their inter-relationships. The Ayurvedic period constitutes the most flourishing and fruitful age of ancient India relating to the accumulation and development of chemical sciences which at that time was closely associated with medicine. The physical and chemical theories were intricately associated with the srshti siddhantas propounded in the vedic, upanishadic and darshana shastras. Ayurveda was founded on the theories of cosmic evolution in Darshanas most importantly of Samkhya and Vaiseshika.[1]

Cosmogenesis

The Vedas take the universe to be infinite in size. The universe was visualized in the image of the cosmic egg, Brahmanda. Beyond our own universe lie other universes. Here we come across a few ancient concepts with particular reference to srshti (theories of cosmogenesis) and origin of jagat (universe) with respect to matter and particles and their connection with chemistry.

- Rig veda (10.121.1) mentions Hiranyagarbha reflecting the concept of cosmic egg and origin of universe from an egg.

- Satapatha Brahmana (6.1.3.1-5) propounded a theory of material evolution.[5]

- Chandogya Upanishad mentions about expansion of universe from an embryonic stage called "Anda" (Chan. Upan. 3.19) wherein after period of one year, it burst open into two halves, one of silver and the other of gold. The lower half of silver became earth and the golden half became the sky and higher regions.

- Katha Upanisad (1.2.20) mentioned atoms and molecules.[5]

- Samkhya siddhanta (supported by Yoga sutras of Patanjali) describes the principles of conservation, transformation and dissipation of energy. Additionally the conception of space (desha) and time (Kala) are also discussed.

- Vaiseshika siddhanta propounded the particulate theory of matter (Padarthas) to describe the nature of different substances that make up this jagat.

- Prasastapada had proposed in his Padartha-dharma-sarhgraha that atoms (anu) form - through dyads (dvyanuka) and triads, (tryanuka), gross bodies (`molecules' in modern terminology) and 'this gives rise to different qualities in a substance'.[5]

Thus broadly the origin and composition of matter had the foundations in our ancient texts.

Samkhya-Patanjala Yoga View of Cosmic Evolution

P. C. Ray in the History of Chemistry in Ancient and Medieval India[1] briefly discusses the Indian theories of evolution and their relation to modern concepts of matter and energy. Samkhya-Yoga schools of thought, according to him, describe cosmogony as based on the principles of conservation, transformation and dissipation of energy and the conception of space (desha) and time (kala). Universe, according to Samkhya, evolved out of an unmanifested cosmic nature termed Prakriti or Avyakta, the ultimate ground. It is believed to be made of infinitesimal reals or gunas, representing substantive entities. They are classified under three heads

- sattva - the essence or intelligent matter

- rajas - the energy

- tamas - the inertia or material substance

These three gunas exist together in equilibrium or uniform diffusion in the infinite continuum, Prakriti. Samkhya attributes the character of both quantum (parichhinatva) and continuity or extension (pariman) to both energy and matter similar to modern concepts. Prakriti is in a state of perfect equipoise with all its gunas in equilibrium representing evolution under arrest. A disturbance of this equilibrium through transcendental or magnetic influence exerted by Purusha (the Absolute) on the Avaykta sets the evolutionary process in motion. The disturbance of the original equilibrium in Prakriti led to an unequal aggregation or collection of gunas representing a creative transformation accompanied by evolution of motion (parispanda) according to a universal definite law. Cosmic evolution is two-fold creative as well as destructive, dissimulative and assimilative, catabolic and anabolic in nature. Samkhya principles also show concurrence with the laws of causation, conservation of mass and energy as well as their transformations.

Cosmic Evolution View in Upanishads

According to this theory, the universe existed in the beginning in a highly refined or potential form like a seed or an embryo with grosser form of apa (water) forming an egg. The egg after a period of maturation broke into two pieces giving rise to the celestial and earthly worlds.[1]

Hiranyagarbha signifies the 'golden womb' or source of creation. Described as the cosmic entity it represents the potential and creative force behind worldly existence. Hiranyagarbha is the Prana, the vital force, the first manifestation as per Chandogya Upanishad. The whole cosmos is governed and activated by Prana.[6]

Atomistic Conception of Matter

Important concepts of physics and chemistry studied in modern times were proposed discussed and debated in ancient times primarily in Samkhya and Vaiseshika darshanas. Most notably enumeration of all knowable or sensorial objects called Padarthas are categorized and their attributes are described in Samkhya, Nyaya-Vaiseshika, darshanas and in Ayurveda samhitas.

Elemental nature of Matter

The Samkhya theory posits that the world is a product of ordered evolution from an original undifferentiated Prakriti, and one becoming many. The Vaiseshika darshana propounds that the world arises out of atoms combining together in various ways, i.e., many becoming one.

According to the Samkhya school's theory of matter,[7] tanmatras are five subtle elements or infra-atomic particles imperceptible to the human senses as a result of continued differentiation and unequal aggregation of gunas from Prakriti as explained above during evolution. These subsequently gave rise, by the same process, to five grosser elements - the Panchamahabhutas namely, akasa (space or ether), vayu (air), tejas (fire), apa (water), and bhumi (earth). They are regarded as representing five abstract principles, or rather a classification of substances on the basis of their properties and states of aggregation. Earth, water and air may be viewed as comprising all the so-called elements or compounds of chemistry.

- Bhumi or kshiti typifies all solids

- Apa typifies all liquids

- Vayu typifies all gases

According to Samkhya, atoms (Anu-s) of these grosses elements are composite units made up of infra-atomic particles, the tanmatras.

Chemistry in Ancient India

In ancient India, chemistry served medicine on one hand - in the preparation of a number of medicines—and technology on the other—for preparing colors, steels, cements, spirits, etc. While knowledge of metals and oxides was prevalent, of the metallic medicines, mercury was particularly popular. In Rigveda there is a mention of gold, silver, copper, bronze among metals or metallic objects.[1] The Ramayana and the Mahabharata mention weapons with arrowheads coated with a variety of chemicals, indicating their knowledge of Alchemy. Various chemical processes generally described in the ancient treatises are those of extraction, purification, tempering, calcination, powdering, liquefying, precipitation, washing, drying, steaming, melting, filing, etc. Later, all these processes were applied to various metals, using special apparatuses or yantras and reagents and heating to different degrees—high, average and low.[8] Chemistry was vigorously pursued in India during the Mahayana phase of activity of Buddhism as seen from the text Rasaratnakara ascribed to Acharya Nagarjuna.

Classification of Chemical Substances

The well-known rasashastra texts like the Rasahrdaya, the Rasarnava, the Rasaratnasamuccaya and the Rasaprakasasudhakara have classified the chemical substances into[9]

- Maharasas: They are a group of minerals which have been recognized as most useful for the potentiation of the rasa namely Mercury or Parada.[10] They are eight in number, Abhraka (Mica; Double silicate of aluminium and Potassium or sodium), Vaikranta (Tourmaline; K2OAl2O36SiO2), Makshika (Chalcopyrite/Copper pyrite; Cu2S, Fe2S3), Vimala (Iron pyrite; Fe2S3), Shilajatu (Black bitumen or mineral pitch), Sasyaka (Copper sulphate/blue vitriol; CuSO4 7H2O), Rasaka (Zinc ore; ZnO, ZnS, ZnCO3), Chapala (Bismuth/selenium).

- Uparasa: These drugs are not equivalent to Parada, but properties of this group of drugs possess less gunas than Parada and indicate usefulness in different procedures of parada or its action towards parada.[11] The eight uparasas are: Gandhaka (Sulphur; S), Gairika (Ochre; Fe2O3), Kasisa (Ferrous sulphate/ green vitriol; FeSO47H2O), Kankshi (Potash alum; K2SO4 Al2(SO)324H2O), Haratala (Orpiment, yellow arsenic; As2S3), Manahshila (Realgar; As2S2), Anjana (Collyrium), Kankushta (Gambose tree extract).

- Dhatu: Dhatus are the drugs which are been extracted (removed forcedly) from their ore, (by melting or process of distillation) similarly the diseases are removed forcedly from the body by them so they are called as Loha.[10] Here usually seven metals are named: svarna (gold), rajata or tara (silver), tamra (copper), loha (iron), naga (lead), vanga (tin) and yasada (zinc). But, the three alloys (misraloha), viz. brass (pittala), bell-metal (kamsya) and a mixture of five metals (vartaka), also come under the category of dhatu. There are textual differences of which metals comprise metals. Rasarnava mentions six metals including copper but Rasaratnasamuccaya not according a place to copper among the dhatus.

- Ratna: The ratnas generally are precious gems. They are of mineral & animal origin which are found in rocks and are formed during the crust formation of the earth. They are durable, colorful & rare and the most valuable entity.[11] These are classified on the basis of; structure, relation to the planets, opacity & transparency, beauty and scarcity. The principal gems used by the rasavadins are: vaikranta (also classed under maharasa), suryakanta (sun-stone; aventurine feldspar mainly containing silicate of sodium and potassium with disseminated particles of red iron oxide which cause fire-like flashes of colour), candrakanta (moon-stone; a type of feldspar containing silicates of aluminium, sodium, potassium, calcium, barium, etc., which possesses a bluish pearly opalescence), hiraka (diamond), mauktika (pearl), garudodgara (emerald), rajavarta (lapis lazuli), marakata (topaz), nila (sapphire) and padmaraga (ruby).

- Visha: Rasarnava appears to be the first text to mention about Visha and Upavisa classification. They are useful in rasakarma and rasabandhana. Rasamanjari, Rasendrachintamani, Rasa jala nidhi have explained 18 kanda visha. They are- Kalakuta, Saktuka, Vatsanabha, Shringika, Mustaka, Halahala, Haridra, Mayura, Binduka, Sunama, Shankhanabha, Sumangala, Pushkara, Bhramara, Karkotaka, Shuklakanda, Raktashringi, Visha or Chakra.[11]

- Sadharana rasas: It is explained only by Rasaratnasamuchaya.[10] They are Kampillaka (Mallotus philippinesis Muell-arg), Gouripashana (Arsenious oxide; As2O3), Navasadara (Ammonium chloride; NH2Cl), Kapardika (Cowries), Agnijara (Amber), Girisindura (Red oxide of mercury; HgO), Hingula (Cinnabar; HgS), Mruddarashringa (Litharge; PbO).[11]

According to tradition, the maharasas and the uparasas are classified in the order in which they find their usefulness with reference to mercury (rasendra). There is also a view that mercury alone has the appellation of rasa, and all the others are called uparasas. Some of the texts differ from one another in the number of maha- and uparasas as well as the substances comprising them. While the Rasaratnasamuccaya gives the above classification, the Rasaprakasasudhakara, considers rajavarta (lapis lazuli) as a maharasa in the place of capala.

Yantras

Many Rasashastra texts carefully spell out the layout of the laboratory, with four doors, an esoteric symbol (RASALINGA) in the east, furnaces in the southeast, instruments in the northwest, etc termed as Rasashala.

Traditional Chemical Practices in India

The industries which sustained on chemical process may be classified broadly under the following headings.[12]

- Ayurvedic Preparations: medical preparations including purificatory processes of mercurial compounds involved chemical reactions and apparatuses are discussed in Rasashastra and Rasayana.

- Chemical arts and crafts: they include the following

- Pottery: Involves prolonged heating, fusion, evaporation, and treatment of minerals and pigments for coloring and art.

- Bead and Glass making: Glass is a solid fused mixture of lime, alkali, sand and metallic oxides. They were coloured by adding colouring agents like metal oxides. The Ramayana, Kautilya's Arthashastra, Brihatsamhita mention glass being used. Evidences of glass slag and glazing are found in Hastinapur, Takshila, Nevasa Kolhapur, Maheshwar and Paunar.[2]

- Jewellery making

- Dyeing: Numerous dyes from vegetable and mineral sources, use of mordants for textiles, craft paints which are relevant both in textile industry and chitrakarma or art of painting. The principal dyeing materials were turmeric madder, sunflower orpiment, cochineal, lac and kermes. Some other substance having tinting properties were Kampillaka, Pattanga and Jatuka. Chemistry of dyeing was well developed with the identification of acidic and basic natures of dyes and use of mordants especially for textiles.[2]

- Cosmetics and perfumes: Brhatsamhita mentions a large number of references to cosmetics and perfumes used in worship and for human enjoyment. The Bower Manuscript (Navanitaka) contained recipes of hair dyes which consisted of a number of plants like indigo and minerals like iron powder, black iron or steel and acidic extracts of sour rice gruel. Gandhayukti gave recipes for making scents, mouth perfumes, bath powders, incense and talcum powder.[2]

- Paper and Ink industry: In ancient India knowledge spread verbally through the word of mouth from the teacher to the disciple, hence it was called Shruti. But with the discovery of scripts, written records gradually replaced the verbal transmission of thought.[13] Paper, as a writing material, was hardly known in India before the 11th century AD. Al-Biruni writes, "it was in China that paper was first manufactured, Chinese prisoners introduced the fabrication of paper in Samarkand, and thereupon it was made in various places, so as to meet the existing want".

- Fermentation technology: Approximately 610 Mantras of ninth Maṇḍala of Ṛgveda says that they were preparing drinks like Soma (Ṛgveda-1.116.7& 10.119.3) by the process of fermentation and the same was used in several religions ceremonies and social gatherings.[14] Barks of plants, stem, flower, leaves, woods, cereals, fruits and sugarcane were some of the sources for making these liquors.[2]

- Building materials: Mortar and Cement using limestone, gypsum and their modified forms are mentioned as the building materials used in ancient times.

- Tanning of leather:

- Mineralogy (धातुशास्त्रम्) or the study of Minerals, broadly involves mining of metal ores such as those of gold, silver, copper, lead, tin, zinc and iron and preparation of alloys such as bronze, and brass. A very comprehensive account of ores, minerals and metals with their extraction and working, their alloys is found in the Arthashastra. There was wide usage of metals for ornaments, utensils, warfare weaponry, coinage, and preparation of medicines.

Chemical Arts and Crafts

Dyes, Mordants and Pigments

Archeological and literary evidences prove that the art of dyeing was practiced since early days of Indian civilization. A dye is a colored substance which imparts more or less permanent color to other materials. Colored substances usually organic chemical compounds were used for textile dyeing. Dyes which are prepared in the form of powder, paste or solution are utilized generally in coloring cotton, wool, silk and cloth of natural fibres, in cosmetics and manufacture of ink etc. Many soluble dyes are converted into pigments by forming insoluble salts (ex - by replacing sodium in a dye salt with calcium) for use in lacquers, paints etc. Dyes were also used for artificial coloring of food items and soft drinks. They are also used for coloring hair, fur, metals etc.

Glass Industry

Generally, glass is produced by melting a mixture of silica (sand: about 75%), soda (about 15%) and calcium compound (lime: about 10%) with the desired metallic oxides that serve as coloring agents.[15] Origin of glass is shrouded in mystery and scholars note that it is difficult to pinpoint the exact period. Modern archeological evidence proved that Mesapotamia, Egypt and India made various siliceous and glazed materials including faience (glazed siliceous ware), glazed pottery and glass.[3]

Fermentation Technology

Fermentation is a particular method of digesting of selected substances that leads to chemical transformation of organic substances into simpler compounds by the action of fement.[16]

Generally fermentation quickly sets in substances of high sugar-content. Hence fermentation technology started in different parts of the old world with sweet-substances, be it vegetable or animal product. In Egypt honey was utilized first for preparation of intoxicating drink by fermentation. In Bharat, Soma juice, a sweet substance formed the first article of fermentation by the Vedic people. Although the technique or art of fermentation has been "self generated", the process may have been observed and used in remote past.

Milk products, like, curd (dadhi) requiring fermentation for changing of milk into such coagulated substance, was a very popular food article even in the Rigveda. The technique of curdling milk occurs in a number of texts connected with the Yajurveda. In the rituals Soma juice preparation involved preparing a sweet concoction for divine offering; while "sura" was another noted fermented product (a product of cereal and honey).[16] They were also used in dyeing, mixing and dissolving operations and for binding and distilling mercury. In Sushruta Samhita, alcoholic beverages were referred to as 'Khola.'[2]

In Arthashastra we find various kinds of liquors described:[1]

- Medaka is prepared from the fermentation of rice

- Prasanna from the fermentation of flour with the addition of spices and fruits

- Asava is derived from fermentation of sugar mixed with honey

- Arista

- Maireya is derived from fermentation of jaggery mixed with long and black pepper or triphala (ayurvedic preparation)

- Madhu is obtained from fermentation of grapes

Kinva or ferment is prepared from boiled or unboiled paste of masha (Phaseolus radiatus), rice and morata (Alangium salviifolium) and the like.

Chemistry in Minerals and Metals

Many processes involved in extraction of metals from ores to their purification deal with advanced knowledge of chemistry. Many ancient and medieval texts reveal that people had this knowledge as outlined below.[5][17]

- Rasashastra: The development of Rasashastra took place with regards to the processing and the use of heavy metals such as mercury, metals, minerals and many of their compounds for alchemical as well as therapeutic purposes. Many new methods/procedures/techniques for the treatment of mercury, metals/minerals were developed to convert these into pharmaceutically most suitable forms/compounds which are non-toxic, highly absorbable and most effective in therapeutics. Alchemical experiments (Lohavedha) were initially explored to remove poverty from the world by the monk of Buddhist order, Nagarjuna and his followers.[18]

- Therapeutic Potential: Although alchemic purposes of minerals were popular in earlier days, as Ayurveda developed utility of metals and minerals in therapeutics became prominent as seen in Charaka and Sushruta samhitas. Acharya Charaka mentioned three Maharasas (Makshika, Shilajatu and Sasyaka) and all eight Uparasas (Kankushta)[19] in his classic text. Interestingly, information on Sadharana rasas was not found in the classic. In addition to these minerals; information on certain salts (lavana dravya), alkaline substances (ksara dravyas) and calcium containing material (jantava dravya) etc. are also found described.[20]

- Chemical Apparatus: A large number of equipment, crucibles, furnaces etc., for processing of minerals and metals are described (Rasarnava). Rasaratnasamucchya contains description of several kinds of crucibles made of fireclay (vahnimrttika), funaces, implements and equipment to be used in the alchemical laboratory.

- Flame tests: Specific colors of flames are due to specific salts of copper, tin, lead (Rasarnava 49). This test is also practiced in present day as preliminary test to identify the chemical compounds. According to Rasarnava - copper gives blue flame; tin, pigeon-colored; lead, pale; iron, tawny color of flame.

- Extraction of Copper: Procedures were described for making copper metal from makshika (7.12-13) vimala (7.20-21) sasyaka (7.41-44) in Rasarnava text. While makshika and vimala are identified as pyrites (Copper pyrite ores) sasyaka is copper sulphate. All three products yielded Tamra or copper. Copper was discovered long before the Daltonian chemistry came into existence.

- Corrosion: Six metals were arranged in the increasing order of corrosion (Rasarnava 7.89-90) - gold, silver, copper, iron, tin and lead. Sulphur was highly reactive with most of the metals.[5]

- Chemical Processes: Reduction-Oxidation in mineral-metal-metaloxide systems, conversion to sulphides were described in Rasaratnasamucchaya text. For preparation of pharmaceutical grade products for human consumption, many intermediary operations were described: purification of the mineral, metallic extraction (satvapaatana), liquefaction, distillation, incineration etc were performed.

- Preparation of Alloys: Mishra-loha or mixed metals were prepared. Alloys of five metals (Pancha-loha) which is used till date to prepare auspicious idols and eight metals (ashtadhatu) were developed.

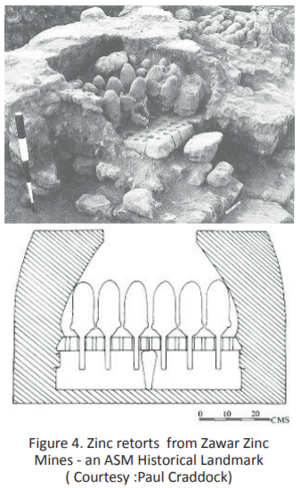

- Zinc Technology: The Zawar zinc technology produced high-zinc (28%) brass alloy not produced anywhere else in the rest of the world. It is the earliest firm evidence for production of metallic zinc in the world. The zinc retorts found in Zawar were similar to those described in Rasaratnasamucchyaa and by Nagarjuna in his Rasaratnakara. The text gives details of the distillation process of zinc by tiryakpatanayantra (distillation by descending) which is totally an ingenious method where the zinc vapor formed after smelting zinc ore (in specifically designed retorts with condensers and furnaces) could be drastically cooled down to get a melt that could solidify to zinc metal.[17]

- Bidri Alloy: The alloy produced in the South Indian town of Bidar, contained Zinc (76-98%), Copper (2-10%), at times Lead (1-8%), tin (1-5%) and trace of Iron. Darkening of the Bidriware made was done by applying a paste of ammonium chloride, potassium nitrate, sodium chloride and copper sulphate. Several impressive vessels, ewers, pitchers, vessels and huqqa bases were made of bidri ware with patterns influenced by the fine geometric and floral patterns and inlayed with gold and silver metals.

Purification Processes in Ayurveda

The detoxification or purification process of any toxic material used for medicinal purposes is termed as “Śodhana”. The process is specially designed for the drugs from mineral origin; however, it is recommended for all kinds of drugs to remove their doṣās (impurities or toxic content). The concept of Śodhana in Ayurveda not only covers the process of purification/detoxifcation of physical as well as chemical impurities but also covers the minimization of side effects and improving the potency/therapeutic efficacy of the purified drugs.[21] The minerals or metals are invariably subjected to purification processes in Ayurvedic preparations and the processes are complicated ones. Though these processes are meant for ‘purifying’ the substances, more often than naught, some extraneous material is added onto them. In general, purification means, according to the rasasastra texts, removal of the deleterious principles present in the naturally occurring substances, so that they become fit for internal use.[3] Examples include

- Sulphur is purified by melting it in the medium of cow’s ghee and straining the molten mass through a cloth into milk or the juice of Bhrhgaraja kept in a pot. It is then washed with warm water and the process is repeated several times. Purification of sulphur is considered necessary as otherwise the impure sulphur, when taken in, would produce harmful effects such as loss of beauty, strength and vision. There are many methods for purification of sulphur using various materials.

- Mica is purified by heating it strongly and adding the hot powdered substance into a mixture of sour gruel, cow’s urine, decoction of the three myrobalans, cow’s milk, etc and the process is repeated seven times.

- Vaikranta is purified by boiling it with the decoction of kulattha (horsegram).

- Purification of mercury involves eight to eighteen methods. Mercury is purified by rubbing it for three days with the decoction of certain plants like kuman (Aloe indica), citraka (Plumbago zeylanica) and red mustard, or by rubbing it with lime and filtering through a cloth. Thereafter it is again rubbed with some quantity of garlic and common salt, and washed.

- The gems are purified by subjecting them to the action of the ‘vapours’ of a plant called jayanti.

It should be noted that these methods form the basis of purification of materials in Ayurvedic preparations and are lately studied for the chemical processes involved in them.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 Ray, P. (1956) History of Chemistry in Ancient and Medieval India, incorporating the History of Hindu Chemistry by Acharya Prafulla Chandra Ray. Calcutta: Indian Chemical Society

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Purwar, Chhavi. Significant Contribution of Chemistry in Ancient Indian Science and Technology. International Journal of Development Research Vol. 06, Issue, 12, pp.10784-10788, December, 2016

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Bose, D. M., Sen, S. N., & Subbarayappa, B. V. (1971). A concise history of science in India. New Delhi: Indian National Science Academy. pp. 274

- ↑ Ray, P. C. (1903). A History of Hindu Chemistry: From the earliest times to the middle of the sixteenth century A. D. (2nd ed., Vol. 1). The Bengal Chemical & Pharmaceutical Works Limited. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.39319/mode/2up

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Minerals and Their Exploitation in Ancient and Pre-modern India by Prof. A. K. Biswas

- ↑ Chandogya Upanisad (S. Lokeswarananda, Trans.). (1995). Sri Ramakrishna Math.

- ↑ Ray, P. (1956) History of Chemistry in Ancient and Medieval India, incorporating the History of Hindu Chemistry by Acharya Prafulla Chandra Ray. Calcutta: Indian Chemical Society

- ↑ Chattopadhyaya, D. (1982). Studies in the history of science in India (Vol. 1). Editorial Enterprises.

- ↑ Bose, D. M., Sen, S. N., & Subbarayappa, B. V. (1971). A concise history of science in India. New Delhi: Indian National Science Academy. pp. 322-326

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Bhagwat, V. S. R., Kurkute, B. R., Shinde, B. T., & Tapare, S. K. (2017). CLASSIFICATION OF RASADRAVYAS IN RASASHASTRA. World Journal of Pharmaceutical Research, 6(4), 792–802. https://doi.org/10.20959/wjpr20174-8226

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 G. T., C., Geethesh, R. R., & Angadi, R. (2018). Collocation Of Rasa Dravyas – An Exploration. International Ayurvedic Medical Journal, 6(9), 2102–2108. http://www.iamj.in/posts/images/upload/2102_2108.pdf

- ↑ Danino. Michel, Technology in Ancient India

- ↑ Tiwari, L. (n.d.). History of paper technology in India.

- ↑ Jena, D. (2021). Concept of chemical science in Vedic literature. International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development, 5(4), 43. https://www.ijtsrd.com/papers/ijtsrd41144.pdf

- ↑ Story of Glass in India & the World by Pankaj Goyal

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Mira Roy. (1997) History of Technology in India, Vol. 1, From Antiquity to c. 1200 A.D. by A. K. Bag. New Delhi: Indian National Science Academy. (Chapter Fermentation Technology : Page 437)

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Srinivasan, Sharada and Ranganathan, Srinivasa. (2013) Minerals and Metals Heritage of India. Bangalore:National Institute of Advanced Studies.

- ↑ Joshi, Damodar. (1997) History of Technology in India, Vol. 1, From Antiquity to c. 1200 A.D. by A. K. Bag. New Delhi: Indian National Science Academy. (Chapter Mercurial and Metallic Compunds: Page 256)

- ↑ Charaka Samhita. Ayurveda Dipika Commentary by Chakrapanidutta. Varanasi: Chaukhambha Surbharati Prakashan (2000). (Chikitsa Sthana 7/111 pp 456).

- ↑ Chandrashekhar. J., et. al., Therapeutic Potentials of Minerals in Ancient India : A Review through Charaka Samhita. J Res Edu Indian Med, Jan - Mar 2014; Vol. XX (1): 9-20

- ↑ Maurya, S. K., Seth, A., Laloo, D., Singh, N. K., Singh Gautam, D. N., & Singh, A. K. (2015). Śodhana: An Ayurvedic process for detoxification and modification of therapeutic activities of poisonous medicinal plants. Ancient Science of Life, 34(4), 188. https://doi.org/10.4103/0257-7941.160862